A journey into a collection of 19th and early 20th century American football memorabilia.

Monday, December 9, 2013

Thursday, November 21, 2013

1890s Richard Harding Davis Photo / Mrs. Walter Camp

This photo of Richard Harding Davis (1864

-1916), from the first half of the 1890s, is inscribed to Mrs. Walter Camp. Davis corresponded with both Walter Camp and

his wife, sometimes writing to either one on the same day. Much of this

correspondence still exists in various archives and collections and we were

lucky enough to have obtained photocopies of letters of interest to us, specifically

from the Special Collections Library of The University of Virginia.

Davis and his

brother were visiting the Camp’s home in Connecticut when they came up for the Yale bowl dedication

in 1914. After this visit Davis in the attached letter states “I scouted around

and was greatly flattered to find myself among your friends (referring to the

photo he sent to Mrs. Camp that was hanging with other photos in their home). I

hate to think when that picture was taken.” (He likely sent this in the early

1890s in return for the Camps having sent him a photo of Walter and his son

(another letter in the collection references this). It was very exciting for Jacob and I to have tied this photo and

this letter together during our research.

The Camp home on Gill Street where the photo hung. The Camps resided here from 1888 - 1905.

Recounting Davis, Bill Edwards said of him “He was one of the

leaders at Lehigh (Davis actually scored their first touchdown) who first

organized that University’s football team. He was a truly remarkable player.

What he did in football is well known to the men of his day. He loved the game;

he wrote about the game; he did much to help the game.”

Davis is considered to this day to be the "Father of Lehigh Football."

From his biography, The Reporter Who Would Be King: A Biography of Richard Harding Davis:

“At the turn of the century, Richard Harding Davis was the

most dashing man in America. 'His stalwart good looks were as familiar to us as

those of our own football captain; we knew his face as we knew the face of the

President of the United States, but we infinitely preferred Davis’s”, wrote

Booth Tarkington. Of all the great people of every continent, this was the one

we most desired to see.

The real – life model for the debonair escort of the Gibson

Girl, Davis was so celebrated a war correspondent that a war hardly seemed a

war if he didn’t cover it.

Describing the desperate charge of his friend Theodore Roosevelt

in the Spanish – American War, he produced both a classic of battle reportage

and a legend in American history…

Writers like Jack London, Stephen Crane, Theodore Dreiser,

Sinclair Lewis and Ernest Hemingway tried to emulate him in their lives and

writing.”

Randolph Hearst, taking advantage of Davis' fame, paid him $500.00 to write a single newspaper article on the Yale – Princeton football contest of 1895 (today that would equate to roughly fourteen thousand dollars).

Randolph Hearst, taking advantage of Davis' fame, paid him $500.00 to write a single newspaper article on the Yale – Princeton football contest of 1895 (today that would equate to roughly fourteen thousand dollars).

This letter reads:

Nov 22nd

My Dear Walter,

I must congratulate you on your “Bowl”, and on the way you

gave everyone a chance to see, and be seen. For that spectacle of seventy

thousand human beings rising in the air was one thing I always will remember.

We had a splendid lunch, and were only sorry that we came so late that we

missed a chance to talk to you all.

I scouted around and was greatly flattered to find myself (referring to the photograph he had sent and

inscribed to Mrs. Camp) among your friends. I hate to think when that

picture was taken.

I paid my respects to you this morning in the Tribune.

Again let me say thank you for taking so much trouble over us we are deeply

grateful. I don’t know how much I really owe you for the tickets, but count

upon you to tell me their real cost. Their value to me in the fun and

excitement could not be put into dollars.

With all good wishes always,

Faithfully yours

Richard Harding Davis

A special thank you to the people at the Special Collections Library of The University of Virginia, Charlottesville, for their assistance.

A special thank you to the people at the Special Collections Library of The University of Virginia, Charlottesville, for their assistance.

Friday, November 15, 2013

c 1870 Foot Ball Game Stereoview

C.1870 American "Foot Ball Game" stereoview (Kicking Game / Association Foot Ball). Keene, New Hampshire, Keene High School, Academy Building. Originally an academy, this building was leased as the High School in 1853 and was demolished and replaced in 1875/76.

Several links are attached with further photos and information (the identity of the building and related links were sent to us from Eric Desmond, Milford, MA).

http://books.google.com/books?id=zxQcTFqk3TwC&pg=PA89&lpg=PA89&dq=%22Keene+High+School%22+%22Academy+building%22&source=bl&ots=C-Zy2bEXOE&sig=t7hWhJy2iCV84euLUBrfpBRraPg&hl=en&sa=X&ei=P3XVUqfGMdHlsASSlYDQDA&ved=0CCsQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=%22Keene%20High%20School%22%20%22Academy%20building%22&f=false

http://www.flickr.com/photos/keenepubliclibrary/sets/72157607343332729/

The airborne ball is circled; this is better viewed with a stereo viewer as the ball is quite clear

Tuesday, November 5, 2013

Everett J. Lake / Worcester Polytechnic

Cabinet card of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute football team of 1889. Everett J. Lake (back row, 4th from the left) graduated from WPI in 1890 and then attended Harvard where he continued to play football in 1890, '91 and '92. He was a Walter Camp All-American in 1891. Lake co-coached the Crimson in 1893. He was to become the Governor of Connecticut in 1920.

Friday, November 1, 2013

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

Glenn "Pop" Warner / 1948 Stagg Coaching Award

The Amos Alonzo Stagg Coaching Award, presented by the American Football Coaches Association to Glenn "Pop" Scobey Warner in 1948. This is awarded to the “individual, group or institution whose services have been outstanding in the advancement of the best interests of football." A significant award for one of the most significant figures in American football.

A large and heavy trophy; bronze plaques mounted on wood.

1948 was an unusual year in that three individuals were presented with this award, Gilmour Dobie, Robert Zuppke and Glenn Warner.

Zuppke (Illinois), pictured below, was so proud of his award he displayed it at public showings of his paintings.

Wednesday, October 2, 2013

Winchester Osgood

Outstanding c. 1894 albumin cabinet photo of Osgood with an unusual

bare-arm pose.

More appropriate than giving a straight Wikipedia style

biography, since it exists, is a first hand, period tribute to Winchester Dana

Osgood, by George Woodruff (played football for Yale in the 1880s and his

longest coaching stint was at Penn from 1892 through 1901). This was published

in the book Football Days, written by Bill Edwards.

“When my thoughts turn to the scores of manly football

players I have known intimately, Win Osgood claims, if not first place, at

least a unique place, among my memories. As a player he has never been

surpassed in his specialty of making long and brilliant runs, not only around,

but through the ranks of his opponents. After one of his seventy or eighty yard

runs his path was always marked by a zigzag line of opposing tacklers just

collecting their wits and slowly starting to get up from the ground. None of

them was ever hurt, but they seemed temporarily stunned as though, when they

struck Osgood’s mighty legs, they received an electric shock.

While at Cornell in 1892, Osgood made, by his own prowess,

two or three touchdowns against each of the strong Yale, Harvard and Princeton elevens,

and in the Harvard – Pennsylvania game at Philadelphia in 1894, he thrilled the

spectators with his runs more than I have ever seen any man do in any other one

game.

But I would belittle my own sense of Osgood’s real worth if

I confined myself to expatiating on his brilliant physical achievements.

His moral worth and gentle bravery were to me the chief

points in him that arouse true admiration. When I, as coach of Penn’s football

team discovered that Osgood had quietly matriculated at Pennsylvania, without

letting anybody know of his intention, I naturally cultivated his friendship,

in order to get from him his value as a player; but I found he was of even more

value as a moral force among players and students. In this way he helped me as

much as by his play, because, to my mind, a football team is good or bad

according to whether the bad elements or the good, both of which are in every

set of men, predominate.

In the winter of 1896, Osgood nearly persuaded me to go with

him on his expedition to help the Cubans, and I have often regretted not having

been with him through that experience.

He went as a Major of Artillery to be sure, but not for the

title, nor the adventure only, but I am sure for the love of freedom and

overwhelming sympathy for the oppressed. He said to me “The Cubans may not be

very lovely, but they are humans and their cause is lovely”.

When Osgood, with almost foolhardy bravery, sat on his horse

directing his dilapidated artillery fire in Cuba, and thus conspicuous, made himself

even more marked by wearing a white sombrero, he was not playing the part of

the fool; he was following his natural impulse to exert a moral force on his

comrades who could understand little but liberty and bravery.

When the Angel of Death gave him the accolade of nobility by

touching his brow in the form of a Mauser bullet, Win Osgood simply welcomed

his friend by gently breathing “Well”, a word typical of the man, and even in

death, it is reported, continued to sit erect upon his horse”.

Osgood was an accomplished and award winning athlete, and

although we tend to know him best for his football exploits, he competed in

wrestling, field and track, boxing, crew and gymnastics as well.

1890s Sheet music memorializing Osgood.

Saturday, September 14, 2013

Langdon Lea , William Church Cabinet Card (Inscribed)

We originally owned three copies of this cabinet card and decided on keeping this one for our collection. It is inscribed from Langdon Lea "yours sincerely, "The Kid", and was kept by the grandchildren of William W. Church, as is described on the reverse in red pencil. Church, a Princeton All-American (1896) and Langdon Lea, Princeton, three time All-American (1893, 94, 95). Lea is pictured on the 1894 Mayo Cut Plug set of cards.

For more information and photos on Lea we would recommend the website http://vintageuofm.tripod.com/index.htm/index.html

Pach Bros receipt to W.W. Church for twelve photos of self for $3.00, that may have been for the pictured cabinet card and the others mentioned in the write-up above.

Sunday, September 8, 2013

An Interview with a Football Legend

About two years ago I had the privilege of meeting and

interviewing Pete Varney, a man best known for catching the two point

conversion after time had run out in the most famous of all Harvard – Yale games, the 1968 “Harvard Beats

Yale 29 – 29” tie. A documentary made about this rivalry and this game in

particular came out in 2008. Harvard

Beats Yale, 29 - 29 was a fascinating and well done piece that fans and historians

of the game can earnestly appreciate.

I was most impressed by Varney’s modesty and concern and high

hopes for those that he has coached. Varney is a sportsman in the truest and finest

sense of the word.

I would like to share the following excerpts from my

interview with Coach Varney.

J.L.: As a player, how

intense was the Harvard-Yale rivalry during your playing days?

Varney: Well, it was

something that every player looks forward to after they’re admitted to Harvard.

They know their chief rival is Yale, so you want an opportunity to play in the

game, number one. And, number two, you want to beat them. It’s something you

always remember. Yeah, we beat Yale, that game was great, great game.’ It’s a

conversation piece for the rest of your life with your teammates.

J.L.: During the game

in 1968, Yale was up 29-13 with about two minutes left. Do you remember your

feelings in those final two minutes or what your teammates were saying to rally

everyone together? What was going on in the last couple moments?

Varney: Quite

honestly, Yale had dominated the game up to the last two minutes; they were

just running all over us. The only thing that kept us in the game was

turnovers. Calvin Hill I think had five for the game. The full-back Levi had a

turnover late in the game. It just seemed like momentum had changed; and it was

only for the last two minutes of the game. Everything seemed surreal. Everything

seemed like a tidal wave. It was nothing you could control - it just happened. But

that’s the reason I think everyone says Harvard won 29-29. Because, I think, if

the game had continued, and the flow of the game had continued the way it was,

just in the last two minutes, that we would have won. There was something

magical and mystical about it, that everything just went our way.

JL: When you think

back to that two-point conversation at the end, do you still get as excited

about it?

Varney: It’s always

better to be remembered as the guy who caught it then as the guy who missed it,

that’s for sure (laughs). It was a play that we had run a hundred times that

season successfully. Basically, even though I was as big as I was, I was like

240, they used to split me out so I was away from the interior line of

scrimmage. I was split out like a wide receiver. What they were trying to do

was use my size as an advantage over whoever was going to be covering me. And,

again, we had run it since day one of the season up until that day. Frank

Champy actually came to the huddle - the guy who was quarterbacking then- said,

‘we’re gonna use this, get open, I’m coming to you’. So, after I caught it, I

was relaxed, but up until I caught it, it was kind of a tense moment.

JL: Most people

remember you for your part in the 29-29 Harvard win, but you were also a

prolific baseball player, and you still have a lot of records at Harvard and

also led Harvard to the NCAA Division I World Series league. You were drafted

to play in the majors seven times, and were the number one pick three of those

times. What’s the story with being drafted so many times and your reluctance to

going to the major leagues?

Varney: It was kind

of different back then. Back then, every six months, if you did not sign while

being drafted, you were thrown back into the pool. There was no rule that said

you had to wait three years of college until after your junior year, as there

is now, or until the age of 21. So the rules changed since then. In 1966, I got

drafted by the Kansas City Athletics –and that was Charlie Finley- he offered

me a contract. I said no and went to Deerfield Academy. That was in September.

In January of ’67, I was drafted again. So every six months you were drafted if

you didn’t sign. So, back then, the rule was that every six months, if you

didn’t sign, you went back into the pool and teams could draft you. I think the

rule was changed in the late 1990s. In the 1990s, basically the NCAA and the

major league teams got together and said that throwing these kids back into the

draft every six months was not good for the colleges because the colleges were

signing kids to four year scholarships. So, the NCAA, the colleges, wanted some

protection. If I’m going to invest some money in this scholarship in this kid,

I want him for four years. Well, the only way we could do that is to compromise.

Some of the NCAA and the major league people come together and said, ok, we’re

going to wait until after junior year, if they don’t sign. As soon as they

enter college, they have to either go until the end of their junior year or

turn 21. So that’s the way the rule changed.

It is interesting, everybody remembers me for the 29-29

game, and nobody remembers my baseball career. So there’s the commentary on my

baseball career.

J.L.: So what was it

like to play for the White Sox and Braves?

Varney: Well, I mean, it was a thrill. It’s something

everybody wants to do. I describe my career as having a cup of coffee and not

having the time to add the cream or sugar in it. But, again, it was a

highlight. Your first at bat, your first hit, your first home run, all

highlights of your career, stuff you’ll never forget. You’ve reached a pinnacle

of your profession. You’re one of 1200 people in the world that are playing

major league baseball, so it’s quite an honor. I wish it had lasted a little

bit longer, but so be it.

J.L.: So, you played

professional baseball, but did you ever have any desire to play professional

football as well?

Varney: No. I knew

from day one that I really wanted to be a baseball player. Played football,

loved football, loved the camaraderie of it, loved the physicalness of it,

loved every aspect of it. But, I get a workout with Dallas, and they offer me

$5,000 to sign out of college and I say, ‘no, I’m going to go play baseball.” I

just always assumed in my own mind that I was going to be a baseball player,

not a football player.

J.L.: After your

professional playing career, you became a coach. You went to Narragansett High

School briefly and then came to Brandeis. How did you decide to become a coach?

Varney: I wanted to

pursue my professional career playing baseball, and always in the back of my

mind I wanted to be a coach. I loved my coaches in high school. They were

always tough on me, kind of tough-love stuff. I wanted to do the same thing. I

love baseball, I love kids, I love working with kids, I love teaching the game,

and I just thought it was a natural fit for me. I probably could have done a

lot of other things and made a lot more money, but, for me, I’ve been very

happy with what I’ve been doing.

J.L.: Did you have

any coaches at Harvard or while playing baseball professionally that influenced

you to become a coach, or was it just you wanting to become a coach on your

own?

Varney: Well, again,

since high school, my high school football coaches, my high school

basketball coaches, my high school

baseball coaches - I’ve always respected

them and admired what they were doing, how they were doing it and thought, ‘I

would like to be doing that.’

J.L.: You’ve been

coaching at Brandeis for 29 years, and you’ve brought the Judges (Baseball) to

the postseason in 20 of those seasons. What are some of your favorite memories,

or favorite memory, from Brandeis?

Varney: I think it’s

when I get together with the alumni, we have a golf tournament. It’s one of the

things we do. Seeing the kids come back and seeing the camaraderie they have

with each other, that’s important to me. It’s important to me that they’ve done

very well in their lives and with their families and the occupations that

they’ve chosen. I have seven kids that are now college head coaches, which is

pretty impressive. I’m happy for them, and that they wanted to go into the same

profession as me. I think that’s pretty cool. I have a lot of high school

coaches and teachers now who’ve been through the program… Whatever they’re

doing, they’re doing it well, and that kind of sparks a little bit of pride in

me, that the kids have gone through Brandeis and gotten their education and

have gone on and been successful in life, in their family life and professional

careers.

J.L.: So, I asked you

about your favorite memory from Brandeis, but what is your favorite memory from

your entire sports past?

Varney: My entire

sports past? Well, to rank them: First career home-run, Larry Ger in Shea

Stadium, even though it was against the Yankees. It was when Yankee Stadium was

being refurbished. You know, the 29-29 catch. I don’t know you could rank them:

one, two, three. High school athletics: all of them. Going to the tech tourney and

playing in the Boston Garden. I’ve been very, very, blessed in that all of my

life a lot of my memories are revolving around athletics. So, to rank them, I

don’t know if that’s fair. I can remember crying right after a basketball game

the in the summer at Red Auerbach’s basketball camp. You know, all those

memories conjure up emotions that are very positive about athletics.

J.L.: Many people consider

you to be a celebrity and can recognize your photo. Do you think of yourself as

a celebrity?

Varney: I was part of

a very unique experience. I think there are a couple reasons why people

remember “the game” Both teams were undefeated. I think it was the

only time in the history of the Harvard-Yale game that both teams were

undefeated not only in league play, but in outside play. Both teams were

undefeated and it wound up in a tie! If it hadn’t wound up in a tie, I don’t

know if people would remember it as much as if one team had really beat the

other team. So that’s the significance of the game, I think. I’m very

reluctant. A lot of people have come to me for over 40-some years about the

game and sometimes I don’t feel very good about it because I think I was a

small part of that game. A lot of people did a lot of great things in that game

that season. It happened to be one particular moment in time, that’s all. I

enjoy my relationship with my former teammates; it was a great thrill,

obviously, but to think I’m a celebrity? No, I don’t think that at all. They still

charge me a buck ninety-nine for coffee at Dunkin Donuts.

J.L.: You’ve been

interviewed many times before this. Is there anything else that hasn’t gotten

out in those interviews about your sports legacy or your coaching that you’d

like to say?

Varney: Nope. Like I

said, I’ve been very blessed. I’ve been very fortunate to have some very good student-athletes

over the years. I’ve been very proud of what they’ve accomplished. I haven’t

accomplished anything in my 29 years here [at Brandeis]. Haven’t caught a ball,

hit a ball, thrown a ball. I’m very happy that I’ve had, hopefully, some

positive influence over some young men over the years.

|

| Pete Varney scoring Harvard's historic 2-point conversion |

Friday, August 30, 2013

Important Luckman to Halas Telegram

George Halas, co-founder of the National Football League,

eight-time NFL Champion and owner and coach of the Chicago Bears, relentlessly

pursued Sid Luckman to play football for him in the late 1930s.

Luckman’s achievements at quarterback are numerous; he completed

twelve seasons with the Chicago Bears, earned four NFL Championships, was voted

to five-time All Pro, became the NFL MVP 1943, threw for 14,686 yards career

passing and became a HOF inductee in 1965.

Luckman’s abilities are perhaps best assessed by Bob Zuppke,

the most well-known coach Illinois has ever seen, who said of Luckman, “He was

the smartest football player I ever saw, and that goes for college and pro.”

Halas had seen and followed Luckman’s play for Columbia and set

his sights squarely on him. Luckman, however, was quite insistent during much

of the back and forth with Halas that he had no interest in playing

professional football. This pursuit of Luckman took place in person, in

writing, by telegram and through intermediaries such as Lou Little, Luckman’s

coach at Columbia.

The pictured telegram from Luckman to Halas was part of this

great story.

Addressed to George S. Halas, President Chicago bears

Football Team, 37 South Wabash Ave CHGO, and dated Jun 14, 1939. It reads:

“Sorry but will require a little more time before

final decision. Other plans not related to football still make it impracticable

to say yes to you terms at this time. Many Thanks, Sid Luckman.”

At this time, Luckman was still contemplating working in a family

business and had reservations about his Ivy League background preparing him for

what he knew to be a rough pro game.

As Luckman related the story, Halas (what would have been soon

after receipt of this telegram) visited Sid and wife Estelle at their apartment

in New York for dinner. After the meal Halas presented a contract to Luckman that

he then signed, as he considered the terms “fair and equitable”. Halas made a toast after

the signing, stating to Luckman that “You and Jesus Christ are the only two

people I would ever pay that much money to.”

Sunday, August 25, 2013

Hayward Cushing of Harvard

Hayward Warren Cushing, 1854 - 1934, Harvard '77 and M.S. Played Harvard football for five years, 1875 through 1879. He played in the first Harvard Yale and first Harvard Princeton games. Played against the likes of Walter Camp, O.D. Thompson, J. Moorehead and Frederick Remington. He was considered the leading player for Harvard in 1877 and one of two leading players in 1878. He became a well known Boston Surgeon.

His brother Livingston Cushing, Harvard class of '79 and L.S., played with him on the 1876, 77, 78 and 79 teams, and was captain in 1877 and 1878.

G.W.Pach 1870s cabinet card.

Saturday, August 17, 2013

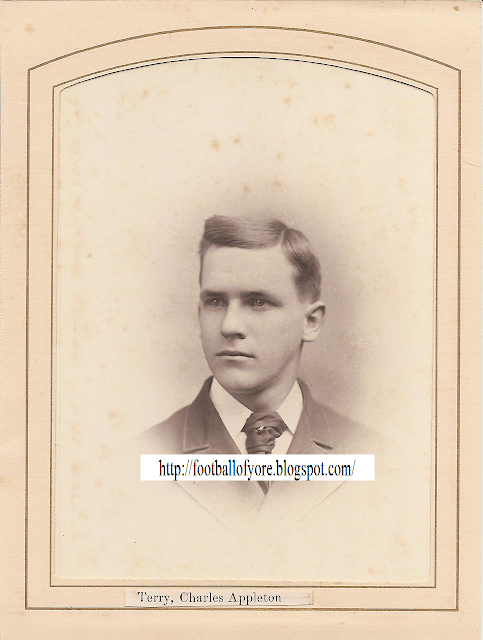

The Beginnings of Amherst Football (Player Cabinet Cards)

We often search for early cabinet cards featuring individual players. Not surprisingly, many (most) important examples of these images may not depict early football players in their actual playing gear, particularly in the case of cabinet cards from the 1870s and early to mid 1880s. For example, if a cabinet card comes from a class album (often the only time you will see an individual’s photograph outside of any existing team portrait), it would normally picture a player in formal attire, or in the cases where they are in uniform it may be that of a sport other than football, such as crew. These cabinet cards are essential research tools in addition to their value as collectible football related ephemera. Obtaining these images is especially relevant and meaningful when researching schools outside of the “big three” of Harvard, Princeton and Yale, and may be your only means in identifying players or early teams. The difficulty however, lies in finding these images, as it can be an extremely difficult task. Oftentimes, when early individual cabinet cards from smaller schools or lesser-known football programs surface, it is doubtful that such likenesses will appear again on the market for a very long time, if they show up at all.

In the 1890s, concurrently with the growing popularity of the game, cabinet cards with football players in uniform became much more common.

Most references on early football will picture a number of such examples of these early cabinet photos.

We would like to share some of these early cabinet photos; individuals who played football during the earliest years of the sport, in this case for Amherst College (from the class of 1879). Amherst organized a college team in 1877 but only played one game against Tufts that year, winning by a score of 8 to 4. Tufts played three games in 1877, losing to Amherst, Harvard and Yale. In 1878, Amherst's first full year of intercollegiate football, most of the individuals pictured below played on the College Fifteen (most colleges were playing 15 men a side); twice against Yale (Walter Camp was their captain), once against Harvard and once against Brown (this was Brown's first intercollegiate game). Several sources include Amherst playing a fifth game in 1878 against Williston, but it is unclear if this was an official or practice game.

Charles Millard Pratt, '79. In

1878 he was a member of the '79 Eleven. He was the first alumnus to donate a

building to Amherst College - the Pratt Gymnasium, erected in 1883. It was

reconstructed several times, first as the Pratt Museum in 1942 and more recently

as the Charles M. Pratt Dormitory, in 2007.

Charles Lyman Goodrich, '79. Captain of the College Fifteen in 1878, member of the '79 Eleven.

Wednesday, August 14, 2013

"On any given Sunday..." Hominy Indians

|

| 1927 Hominy Indians vs. NFL Champion New York Giants Game Ball |

This is one of the few “vintage” footballs in our collection. This particular item was the game ball from a little known and mostly forgotten part of football history. A professional team of Indians from various tribes, playing together as the Hominy Indians (from Hominy, Oklahoma), took on the 1927 World Champion New York Giants (basically a post season barnstorming team made up of mostly New York Giants and other notable players) in an exhibition game that many assumed would be rather dominating for the champions. The Giants had just gone 11-1 during the regular season, absolutely dismantling most of their competition. Over their twelve games, the champions scored a total of 197 points and held their opponents to just 20 points over that stretch. The Giants forced a total of nine shutouts, holding teams like the Pottsville Maroons, Frankford Yellow Jackets, Cleveland Bulldogs, and Duluth Eskimos scoreless. The champions doomed some of the most elite offenses in early football in unparalleled fashion (not to mention what the Giants did to these teams' defenses).

The Indians, while unable to boast such an impressive record against NFL teams, had made somewhat of a name for themselves because they traveled up and down the east coast playing football. The squad had never lost any of their football games, and the Indians had earned a devoted following. Still, however, Hominy was not an NFL-caliber team. And few teams, let alone a team composed of unknown and untested players, could seriously contend with the Giants, the champions of the National Football League and presumably greatest team in the country.

The Indians' fate rested with the great John Levi, who Jim Thorpe called "the best athlete" he'd ever seen. It is difficult to discern what from John Levi's biography is fact and what stems from legend. He is perhaps one of the most storied players from the early years of football. It has been said, for example, that Levi could drop-kick the football, which was rounder and heavier than today’s ball, from the 50-yard line and send it through the goal posts. Legend also has it that Levi could pass the ball 100 yards. While there is no way to confirm these tales, what is certain is Levi's importance to the Hominy Indians and the development of football.

Others on the Hominy team besides Levi, including some who had previously been coached by Jim Thorpe on the Oorang Indians (such as Joe Pappio), would also be essential if the Indians were to pull off a miracle against the Giants.

During their exhibition game on December 27, the Indians and Giants engaged in a ferocious contest in front of over 2,000 fans.

The Hominy squad outlasted the NFL champions and won by a score of 13 to 6, in what became one of the most unexpected upsets in football history.

It is interesting to note that Hominy is the only Indian team to ever defeat an NFL team; not even Carlisle could ever do it. And Hominy did not just take down any NFL squad - they pummeled the champions.

Jacob

and I have been corresponding with Art Shoemaker, of Hominy, Oklahoma, who

researched the Hominy Indians, and through him, we obtained extensive

information on the team. Art is a wealth of information and is likely

the most knowledgeable (and sharing) authority on Hominy and related Indian

football. He is a researcher, author and a true gentleman. We sincerely thank him for his time and efforts.

The game ball is in excellent condition. A beautiful piece of history.

The game ball is in excellent condition. A beautiful piece of history.

Tuesday, August 13, 2013

Alice Sumner Camp: The Woman Behind the Man

|

| The calling card of Mrs. Walter Camp |

One theory on the identity of the individual behind the secretarial Camp signatures that Jacob and I came up with was that Mr. Camp had his wife sign these items. And, having a few Alice Camp signatures in our collection, we thought we'd share a few examples of her handwriting here on Football of Yore - in case any secretarially signed examples can indeed be attributed to Alice.

Alice Camp was a football legend of sorts

and spent countless hours with her husband on and off the field, thoroughly

invested in the game and the players. She was referred to as "Mrs.

Walter" by the Yale players who were often guests at her home. She was recognized for her significant contributions and was even listed as a co-coach on the 25th reunion dinner program of the 1888 Yale Football team. There is an

abundance of information on Mrs. Camp should one decide to delve a little

deeper.

The first example of her handwriting is on her calling card, and

the other is a short note to James Cowan, complete with her full signature, Alice

Sumner Camp, inviting Sawyer for tea and to meet with a "Mrs. Bates."

Both examples we are posting emanated from the collection of James Cowan Sawyer, the son of a former governor of New Hampshire. Sawyer attended Phillips Academy in Andover where he was the manager of the football team in 1889. Sawyer later attended Yale, where he was the manager of the freshman football team, assistant manager of the University Football Association, and held many other positions with various clubs and associations.

Both examples we are posting emanated from the collection of James Cowan Sawyer, the son of a former governor of New Hampshire. Sawyer attended Phillips Academy in Andover where he was the manager of the football team in 1889. Sawyer later attended Yale, where he was the manager of the freshman football team, assistant manager of the University Football Association, and held many other positions with various clubs and associations.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)